Chinese calligraphy definition, known as Shufa (書法) in Mandarin, is one of the most significant and enduring aspects of traditional Chinese culture. It is not merely a method of writing; it is a disciplined practice that reflects the values, philosophy, and aesthetics of Chinese civilization. With a history spanning over three millennia, calligraphy has evolved from early inscriptions on oracle bones during the Shang Dynasty to the highly refined scripts of the Tang and Song dynasties. Each character, stroke, and composition carries meaning beyond mere words, expressing the writer’s personality, ethical values, and intellectual depth.

Traditionally, calligraphy was closely linked with education, governance, and social status. Mastery of this art was considered a hallmark of scholarship, moral integrity, and cultural refinement. Philosophical traditions such as Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism deeply influenced calligraphy, shaping both the techniques and the purposes of writing. Today, while digital communication dominates, Chinese calligraphy remains a living cultural practice, valued for its aesthetic, historical, and meditative qualities. Understanding its definition, history, and cultural significance provides insight into the heart of Chinese civilization and the enduring power of written expression.

Table of Contents

1. What is Chinese calligraphy definition?

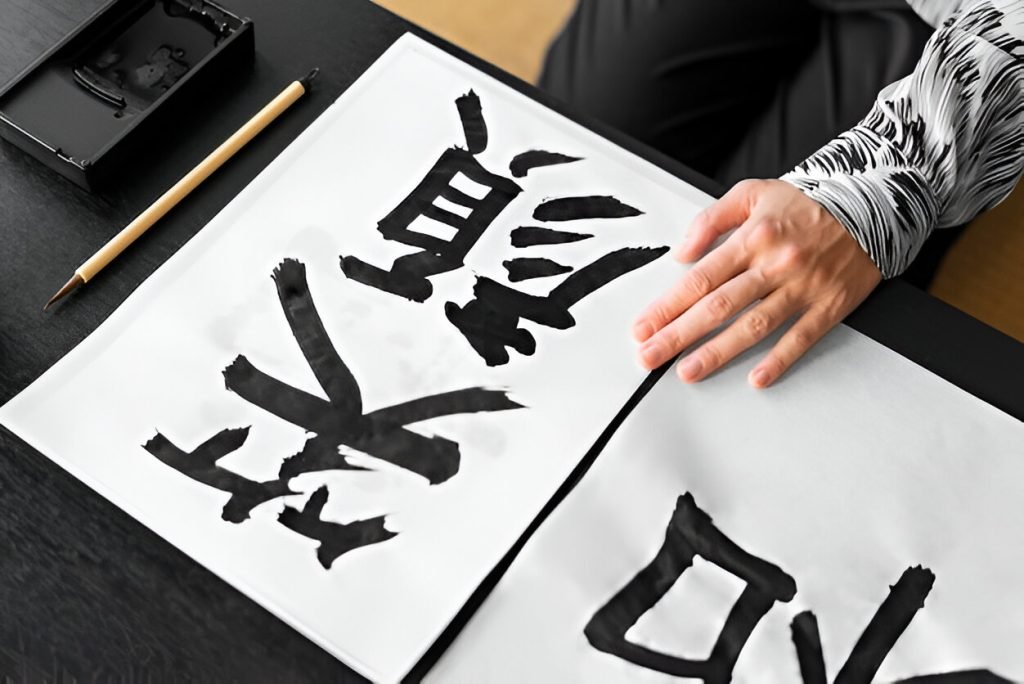

Chinese calligraphy definition is the practice of writing Chinese characters with a brush and ink in a way that emphasizes structure, rhythm, and expression. Unlike ordinary handwriting, calligraphy is a visual art form where each stroke, character, and composition conveys meaning and emotion.

The purpose of calligraphy in traditional Chinese culture extends beyond communication. It was considered a means of cultivating personal character, discipline, and aesthetic sensibility. Scholars, officials, and artists were expected to master calligraphy as part of their education, and the quality of one’s writing often reflected their moral and intellectual capabilities.

Calligraphy involves careful control of brush movement, ink flow, and paper interaction. It is not only a technical skill but also an expressive medium that allows the calligrapher to convey personality, rhythm, and emotion through characters.

2. Historical Roots of Chinese Calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy has a history of more than 3,000 years. Its earliest examples are found in oracle bone inscriptions during the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE). These inscriptions were primarily used for divination, documenting events, and ceremonial purposes.

During the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), writing became more structured with the development of bronze inscriptions on ceremonial vessels. These early scripts laid the foundation for standardized character formation and writing conventions.

The Qin Dynasty (221–206 BCE) introduced Seal Script (Zhuanshu), a more uniform and systematic style used for official documentation. During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the Clerical Script (Lishu) was developed to increase writing speed and readability for administrative purposes.

By the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE), calligraphy had evolved into various recognized styles, including Regular Script (Kaishu), Running Script (Xingshu), and Cursive Script (Caoshu). These scripts reflected a balance of technical skill and artistic expression, becoming central to Chinese education, administration, and culture.

3. The Philosophical Significance of Calligraphy

Chinese calligraphy is deeply influenced by traditional Chinese philosophy. It is a medium through which moral, spiritual, and aesthetic values are expressed.

Confucian Influence

Confucianism emphasizes moral education, discipline, and self-cultivation. Calligraphy was viewed as a tool to cultivate these qualities. Practicing calligraphy required focus, patience, and attention to detail, reflecting the Confucian ideal of personal development and ethical behavior.

Daoist Influence

Daoism stresses harmony with nature and the flow of life. This philosophy encouraged a natural, spontaneous approach to brushwork. The movement of the brush in calligraphy often mirrors natural rhythms, representing Daoist principles of balance, energy, and effortless action (wu wei).

Buddhist Influence

Buddhism introduced mindfulness and meditative practice into calligraphy. Writing characters slowly and intentionally became a form of meditation, promoting inner calm, focus, and spiritual reflection. Calligraphy was often used to transcribe Buddhist texts and sutras, linking writing to spiritual practice.

4. Tools of Chinese Calligraphy

Mastering Chinese calligraphy requires understanding and skill in using the Four Treasures of the Study (文房四寶): brush, ink, paper, and inkstone.

- Brush (毛筆, Maobi): Brushes vary in size, hair type, and flexibility. They allow for precise control of strokes or expressive, flowing movements depending on the script.

- Ink (墨, Mo): Traditionally made from soot and animal glue, ink quality affects the texture, darkness, and consistency of strokes.

- Paper (紙, Zhi): Xuan paper or rice paper is absorbent, allowing for fluid and dynamic strokes. Paper choice impacts the overall appearance and quality of the work.

- Inkstone (硯, Yan): The inkstone grinds ink sticks to prepare liquid ink. It helps control ink density, thickness, and consistency, which are essential for producing balanced strokes.

Each tool has a specific function, and mastering their use is essential for producing high-quality calligraphy.

5. Styles and Techniques

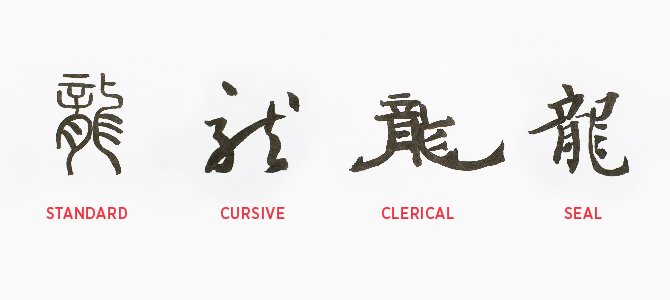

Chinese calligraphy includes several main styles, each with unique characteristics and purposes:

- Seal Script (篆書, Zhuanshu): Earliest formal script, used in official seals and inscriptions. It is symmetrical and uniform.

- Clerical Script (隸書, Lishu): Developed for administrative efficiency. Characters are wide with clear, flat strokes.

- Regular Script (楷書, Kaishu): Standardized, formal script used in official documents and education. Known for clarity and structure.

- Running Script (行書, Xingshu): Semi-cursive style combining readability with expressive brush movements. Often used for letters and literature.

- Cursive Script (草書, Caoshu): Highly expressive, free-flowing script. Focused on speed, rhythm, and artistic expression.

Mastering these scripts requires careful attention to stroke order, proportion, spacing, and brush control. Each style allows the calligrapher to convey different emotions, rhythms, and levels of expression.

6. Cultural Importance in Society

Chinese calligraphy has long held a central role in education, governance, and daily life. It was historically used in the Imperial Examination System to evaluate candidates for civil service, where the quality of one’s writing reflected intellect and discipline.

Calligraphy also played a role in preserving history and communication. Important records, official documents, and literary works were all produced with attention to aesthetics and accuracy. It became a measure of social refinement and intellectual achievement.

Calligraphy in Art and Literature

Calligraphy is often integrated into Chinese painting and poetry. Artists combined inscriptions with visual art to create a fusion of literary and visual expression. This practice emphasized the unity of form, meaning, and aesthetic value, reinforcing the idea that writing and painting are interconnected cultural expressions.

Social Practices

Collectors and scholars historically studied and preserved calligraphy works, passing down cultural and intellectual traditions. The practice of collecting and analyzing calligraphy deepened understanding of language, philosophy, and historical thought.

7. Modern Relevance of Calligraphy

Even today, Chinese calligraphy maintains cultural and educational significance. Schools teach it as part of traditional arts education, and exhibitions showcase contemporary and historical works.

Cultural Preservation

Efforts to preserve calligraphy heritage include competitions, workshops, and museum exhibitions. Recognized as intangible cultural heritage, calligraphy represents a living connection to Chinese history and philosophy.

Calligraphy and Personal Development

Modern practitioners view calligraphy as a tool for mindfulness, focus, and personal growth. It encourages patience, concentration, and reflection while providing insight into traditional Chinese values and history. Calligraphy also finds applications in modern design, bridging cultural heritage with contemporary aesthetics.

Conclusion

Chinese calligraphy definition is more than a method of writing—it is a cultural practice that reflects the values, philosophy, and history of China. Throughout its development, from the inscriptions on oracle bones to the refined scripts of the Tang and Song dynasties, calligraphy has maintained its role as both a practical and artistic pursuit. It serves as a medium for expressing personality, intellectual depth, and ethical discipline, while also preserving the written record of Chinese civilization.

The practice of calligraphy is deeply intertwined with traditional philosophies such as Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism, which shaped the techniques, purpose, and spiritual dimensions of the art. Its tools—the brush, ink, paper, and inkstone—require skill and understanding, while its diverse styles allow for expressive flexibility and creativity. Historically, calligraphy influenced education, governance, art, and literature, and today it continues to hold cultural and educational significance.

By studying Chinese calligraphy, one gains insight into the core principles of traditional Chinese culture, the importance of discipline and focus, and the enduring connection between writing and personal expression. It remains a living tradition, bridging the past and present, and highlighting the timeless value of Chinese cultural heritage.